The Taj Interiors: Interior Decoration

Mausoleum

Also known as Rauza-i-Munauwara, Rauza-i-Muqqadas & Rauza-i-Mutahhara. The mausoleum dominates the entire Taj complex: the architectural effect is that of a strictly ordered progression of elements towards the overwhelming climax of the white marble building. The mausoleum is set at the northern end of the main axis of vast oblong walled complex which descends in hardly noticeable terraced steps towards the river Yamuna. The overall composition is formed of two major components: the mausoleum and its garden, and two subsidiary courtyard complexes to the south.

The Tomb

The central focus of the complex is the tomb. This large, white marble structure stands on a square plinth and consists of a symmetrical building with an iwan (an arch-shaped doorway) topped by a large dome and finial. Like most Mughal tombs, the basic elements are Persian in origin. The base structure is essentially a large, multi-chambered cube with chamfered corners, forming an unequal octagon that is approximately 180 feet on each of the four long sides. On each of these sides, a massive pishtaq, or vaulted archway, frames the iwan with two similarly shaped, arched balconies stacked on either side. This motif of stacked pishtaqs is replicated on the chamfered corner areas, making the design completely symmetrical on all sides of the building. Four minarets frame the tomb, one at each corner of the plinth facing the chamfered corners. The main chamber houses the false sarcophagi of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan; the actual graves are at a lower level.

The Tomb Chamber

The mausoleum represents the culmination of the entire Taj complex, so the inner domed hall represents the climax of the mausoleum. It is the final station in the progress towards the tomb of Mumtaz, and that of Shah Jahan. The large hall, together with the lower tomb chamber over the actual burials below and the outer dome above forms the core of the building. Here all the elements, architecture, furniture, and decoration combine to create an eschatological house for Mumtaz Mahal. Even sound was put to the task of eternity, through one of the longest echoes of any building in the world. The hall has the form of a perfect octagon, 24 feet to a side, with two tiers of eight radiating niches. These niches, termed nashiman (‘seat’), are equal in size but differentiated in their elevations. In those on the cardinal axes the inner wall is open and fitted with a screen which transmits light into the interior of the hall.

The floor is paved in a geometrical pattern consisting of octagonal stars alternating with pointed cruciform shapes, formed by black marble inlaid in white. Around the whole is a border of lobed cartouches of alternating size. The same border-surrounds the cenotaph of Mumtaz (but not the one of Shah Jahan, which was introduced later), it is a variant of a pattern used repeatedly in the Taj complex, most closely paralleled in the border of the terrace surrounding the platform of the mausoleum. Luxurious vases filled with flowers appear here instead of the individual flowering plants of the pishtaq halls outside. The flowers follow botanical species more closely, and one can identify the Mughal favourites, irises, tulips, daffodils and narcissus. They are naturalistic and seductively beautiful, but at the same time they convey the order of the Shahjahani system.

All vases have the same general shape and all are set on little hills with small flowering plants in mirror symmetry on each side. All bouquets follow the same basic tripartite arrangement, with a dominant flower in the centre flanked by mirror-symmetrical groups on each side.

The dados of the side walls of all the niches display triadic vase groups with dominant tulips. The central vase is distinguished by a voluted ornament attached to its upper body and a different flower arrangement: the central tulip of the bunch has its outer petals curved down, and it is flanked by daffodil-like flowers and lilies with curved-back petals.

The Lower Tomb Chamber

From the southern entrance room a stairway covered with a pointed barrel vault leads down to the lower tomb chamber (not accessible to visitors). The rectangular room is entirely faced with marble and has an undecorated coved ceiling. In the centre stand the two cenotaphs that cover the actual graves; they are similar to those above but have different motifs in their decoration.

The lower cenotaph of Mumtaz Mahal has an almost undecorated platform. Its top is again covered with passages from the Qur’an, expressing related themes, promising God’s mercy and forgiveness. On the sides are tiny cartouches containing the Ninety-Nine Beautiful Names of Allah, which express divine attributes such as O King, O Holy, O Peace.

The lower cenotaph of Shah Jahan is also a more simply decorated version of his cenotaph above. The same flowers, namely poppies and plants with yellow lily-like blossoms, appear on the side walls of its sarcophagus element; they are however smaller, and set individually in tiny red cusped cartouches, reflecting the arrangement on the cenotaph of Mumtaz.

The south end displays the epitaph, which is more comprehensive than the version on Shah Jahan’s upper cenotaph:

This is the illumined grave and sacred resting place of the emperor, dignified as Rizwan, residing in Eternity, His Majesty, having his abode in [the celestial realm of] Illiyun, Dweller in Paradise (Firdaus Ashiyani) [posthumous title of Shah Jahan], the Second Sahib-i Qiran, Shah Jahan, Padshah Ghazi [Warrior for the Faith]; may it be sanctified and may Paradise become his abode. He travelled from this world to the banquet hall of eternity on the night of the twenty-sixth of the month of Rajab, in the year one thousand and seventy-six Hijri [31 January AD 1666].

The Screen and the Cenotaphs

The naturalistic decoration of the interior culminates in the central ensemble of the cenotaphs of Mumtaz and Shah Jahan and the screen that surrounds them. It attracts all visitors today with its spectacular flowers and plants inlaid in semi-precious stones.

The perforated marble screen (mahjar-i mushabbak) was set up in 1643 to replace the original one of enamelled gold made by the goldsmith and poet Bibadal Khan on the occasion of the second anniversary of Mumtaz Mahal’s death in 1633, which was obviously deemed too precious. It took ten years to make and cost 50,000 rupees, less than one-tenth of the cost of the gold screen. Since 1994-1995 AD it has been protected from the hands of visitors by an ungainly aluminium grille in a wooden frame.

The screen is octagonal, reflecting on a smaller scale the octagon of the surrounding hall and intensifying the paradisiacal symbolism of the number eight. Overall arrangement and detail follow the principles of Shahjahani system. Each side of the octagon is divided into three by marble frames. The corners are fortified by posts ending in kalasha finials (globes surmounted by a pointed element), an adaptation of a feature of older Indian architecture. The frames are filled with jalis, in which elegantly and intricately wrought plant elements are composed around a central axis – the only instance in the Taj Mahal where jalis are formed of organic plant arabesques rather than geometric forms.

The Indian jali tradition is here brought to one of its highest points. The screen is topped with ornamental crenellations, kanguras, consisting of vase-shaped elements alternating with openwork formed of volutes of acanthus leaves, crowned at their juncture by small vase elements. The entrance arch in the centre of the south side and a corresponding closed arch opposite it in the centre of the north side rise above the screen; they have semicircular heads lined by a moulding terminating in hanging acanthus buds.

Within the screen are the upper cenotaphs of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan – what Lahauri and Kanbo call surat-i qabr, ‘the likenesses of tombs’. As usual in imperial Mughal mausoleums, the actual burials are below, in the lower tomb chamber, under cenotaphs of similar design. The cenotaph of Mumtaz is exactly in the centre of the hall. The larger cenotaph of Shah Jahan was added on its western side, and thus from a formal point of view appears as an afterthought. This placing gave substance to the rumour of the emperor’s burial having been planned not within the Taj Mahal but on the opposite side of the Yamuna in a black marble tomb.

The cenotaphs are aligned north-south, with the head to the north. The bodies were laid in their graves below on their side, with their face turned towards Mecca – which in India is to the westso that they would rise in the correct position at the sound of the trumpets at the Last Judgment.

Each cenotaph consists of a single block of stone, shaped like a sarcophagus, set on a stepped plinth which is placed in turn on a wider platform. The cenotaph of Shah Jahan is characterized as a male tomb by the symbol of a pen case on its top. While the cenotaphs conform to an established Mughal type, no other Mughal, nor any other personage in the Islamic world, was commemorated with such exquisite decoration. The lower cenotaph of Jahangir at Lahore is the only one that comes close; it was created at the same time as that of Mumtaz, probably by the same artists. The decoration of the cenotaphs with hardstone inlay was reserved for mem bers of the Mughal imperial family.

The Decoration of the Upper Cenotaph Of _

Mumtaz Mahal :

The main decoration consists of inlaid Qur’anic inscriptions. Naturalistic plums are confined to the platform, where two types alternate, between borders of hanging blossoms: one has asymmetrically arranged erect funnel-shaped calyxes and buds, the other a perfectly symmetrical arrangement of seven smaller blossoms and buds; both seem to be inspired by lilies and the upper surface of the platform has a framed flowery scrollwork pattern. Inscribed on the top and the sides of the block are Quran’ic verses in formal Sulus script; their common theme is to comfort the soul (of Mumtaz) with the prospect of Paradise.

The epitaph reads: ‘The illumined grave of Arjumand Bano Begam, entided Mumtaz Mahal, who died in the year 1631’.

Shah Jahan :

The cenotaph of the emperor, installed more than thirty years later, in 1666, is similar to that of Mumtaz in shape and decorative organization, but larger, and entirely covered with flowers and scroll work without any formal inscriptions, The only inscription is the epitaph, positioned like that of Mumtaz. The covering of the Emperor’s cenotaph with recognizable poppies are intended to give heightened realism to red flowers as symbols of suffering and death.

The epitaph reads: ‘This is the sacred grave of His Most Exalted Majesty, Dweller in Paradise (Firdaus Ashiyani), Second Lord of the Auspicious. Conjunction (Sahib-i Qiran-i Sani), Shah Jahan, Padshah; may it ever be fragrant! The year 1076 [AD 1666]’.

The Ambulatory Rooms (‘Shish Mahal’)

The central tomb chamber is surrounded by ambulatory rooms on two storeys, which on all but the southern, entrance, side are separated from it by jalis filled with panes of glass – whence the later name,’ Shish Mahal’ (‘Mirror Palace’). These rooms are not accessible to visitors. Cruciform rooms are set on the cardinal axes and octagonal ones on the diagonal axes.

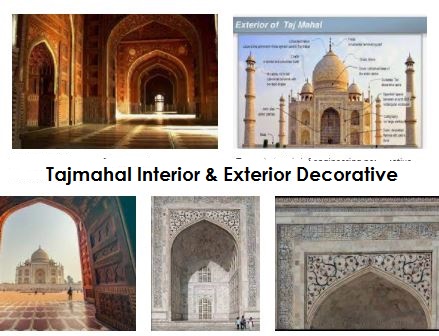

‘The Taj!’ EXTERIORS | A Marvel in Marble

The mosque establishes the form that the Mihman Khana follows. It is based on a standard type which the Mughals took over from the Sultanate architecture of Delhi, namely that of an oblong massive prayer hall formed of vaulted bays or rooms arranged in a row with a dominant central pishtaq and domes. The elevation of mosque and Mihman Khana takes its cue from the great gate, the third monumental subsidiary building of the funerary garden (their relationship is also announced on the overall plan, where they form the points of a compositional triangle).

The Plinth

The mausoleum sits on a plinth, decorated with delicate relief carvings (munabbat kari) of plant elements. This type of ornament, conforming to the principles of sensuous attention to detail and selective naturalism, is reserved for the lowest zone of the building, where it could be immediately appreciated by the viewer. Naturalistic ornament also appears above the plinth, in the spectacular flowering plants of the dados of the pishtaq halls.

The Marble Platform of the Mausoleum (Takhtgah)

Monumental platforms housing the tomb chamber, above the actual burial, had been a prominent feature of Mughal mausoleums. The platform is square and its corners are accentuated by the four minarets which project as five sides of an octagon. It is set off from the paved surface of the terrace by paving with an interlocking pattern of white marble octagons into which are set fourpointed sandstone stars, surrounded by a border with alternating long and short cartouches, a lobed variant of the angular pattern that frames the garden walkways. In the centre of the southern side of the platform, towards the garden, arc two flights of stairs, partly covered by tunnel vaults, which provide the only access from the terrace up to the level of the mausoleum.

In the centre of the other three sides tripartite bait in the form of an open oblong room flanked by two square cells, all covered with coved ceilings, is set into the platform. The central room has three arched openings corresponding to the trefoil-headed blind arches, filled with jalis in the hexagonal pattern found everywhere in the complex; a small rectangular window is cut into the central jali. These cell reached through doors are used for storage, these rooms probably originally served visiting members of the imperial family as a place to retire and rest; or perhaps the Qur’an reciters stayed here when they were not on duty.

The Pishtaqs or Monumental Porches

The pishtaqs embrace two storeys, and in their back walls are superimposed arched doors, larger below and smaller above. Both doors are filled with a rectangular framework containing jalis formed of tiny hexagonal elements in a honeycomb pattern. The setting of the door on the ground floor echoes that of the outer pishtaq arch: it is framed with an inscription band, and its spandrels show a simpler version of arabesques. The door of the upper floor is integrated into the transition zone of the half-vault, formed of arches.

The Dome

The marble dome that surmounts the tomb is the most spectacular feature is accentuated as it sits on a cylindrical “drum” which is roughly 23 feet high. Because of its shape, the dome is often called an onion dome. The top is decorated with a lotus design, which also serves to accentuate its height. The shape of the dome is emphasised by four smaller domed chattris (kiosks) placed at its corners, which replicate the onion shape of the main dome. Their columned bases open through the roof of the tomb and provide light to the interior. Tall decorative spires extend from edges of base walls, and provide visual emphasis to the height of the dome. The lotus motif is repeated on both the chattris and guldastas. The dome and chattris are topped by a gilded finial, which mixes traditional Persian and Hindu decorative elements.

The Minarets (Minar)

Four minarets each more than 130 feet tall, display the designer’s penchant for symmetry is set at the corners of the platform of the mausoleum and complete the architectural composition. They were designed as working minarets, a traditional element of mosques, used by the muezzin to call the Islamic faithful to prayer. Each minaret is effectively divided into three equal parts by two working balconies that ring the tower. At the top of the tower is a final balcony surmounted by a chattri that mirrors the design of those on the tomb. The chattris all share the same decorative elements of a lotus design topped by a gilded finial. The staircase opens through rectangular doors onto the balconies, and windows providing light and ventilation. Although these are covered with grilles, the interior is full of bats, which makes the ascent difficult because they react with hysteria to a person’s entrance. The minarets create a special aura around the mausoleum, and the Mughals interpreted them as mediators to the upper sphere. For Lahauri they were ‘like ladders to the foot of the sky’ and to Kanbo they appeared as ‘accepted prayers from the heart of a pure person which have risen to heaven’. The minarets were constructed slightly outside of the plinth so that, in the event of collapse, (a typical occurrence with many tall constructions of the period) the material from the towers would tend to fall away from the tomb.

The Riverfront Terrace (Chabutra)

The terrace of the Taj Mahal is the most ambitious ever built in a Mughal riverfront garden scheme, unprecedented in size and decoration and one of the most impressive platforms in the history of architecture. Its full splendour is displayed towards the river, where it forms an uninterrupted red sandstone band 28 feet 6 inches high from the lowest visible plinth and 984 feet long, with elaborate decoration in relief and inlay work. The riverfront terrace was the first part of the Taj Mahal complex to be built. All the areas are differentiated by their paving in varying geometrical patterns of dark and light sandstone.

The Roof Terrace

Staircases covered by pointed barrel vaults lead from the ground floor to roof level. On the upper floor they set out from the corridors between the central hall and the two southern corner rooms, and emerge at the sides of the east and west pishtaqs. As in the great gate, there is a system of ventilation shafts. The terrace is dominated by the outer dome, which rises with its high drum like an independent tower in the centre. The transition zone between drum and dome is ornamented with a moulding with a twisted rope design in inlay. At its top is a crowning element formed of lotus leaves, which had become a standard motif of Indian Islamic architecture. From this rises a finial formed of superimposed gilded bulbs topped by a crescent.

The dome is surrounded by four chhatris which, as the Mughal historians tell us explicitly, form the third floor of the octagonal corner chambers, in the shape of octagonal pillared domed structures. The roof terrace is surrounded between the pishtaqs by a high parapet, and its corners are accentuated by the guldastas terminating the shafts on the corners of the mausoleum.

The Main Finial

The main finial was originally made of gold but was replaced by a copy made of gilded bronze in the early 19th century. This feature provides a clear example of integration of traditional Persian and Hindu decorative elements. The finial is topped by a moon, a typical Islamic motif whose horns point heavenward. Because of such placements on the main spire, it creates a trident shape, reminiscent of traditional Hindu symbols of Shiva.

The calligraphy on the Great Gate reads “O Soul, thou art at rest. Return to the Lord at peace with Him, and He at peace with you.”